An STO, or Security Token Offering uses blockchains distributed encrypted ledger in the sale and transfer of a company’s stock or membership units in an LLC.

Because this token is a security under U.S. law, the rules and regulations must be followed. There could be civil or criminal liability for individuals that do not deal properly with securities. Blockchain does not provide a work-around to U.S. securities or tax laws.

There are several exemptions from Securities Act registration that make it more practical and affordable to raise funds.

In 1982, the SEC combined the exemptions for private placements and small offerings into a set of rules known as “Regulation D”. These rules give guidance on when an offering will qualify for the §4(a)(2) private placement exemption (Rule 506) and create another exemption for smaller offerings as authorized by §3(b)(1) and more recently §28 (Rule 504, amended in 2020).

With Rule 506, there is a 506(b) or 506(c) option. 506(b) will be discussed in another article.

The Rule 506(c) exemption to Securities Act Registration used to fundraise.

It is a private placement that allows an unlimited amount of funds to be raised from accredited investors. A company may advertise to everyone with 506(c), so long as equity is only sold to accredited investors.

“Rule 506(c) permits issuers to broadly solicit and generally advertise an offering, provided that:

- all purchasers in the offering are accredited investors

- the issuer takes reasonable steps to verify purchasers’ accredited investor status and

- certain other conditions in Regulation D are satisfied

Purchasers in a Rule 506(c) offering receive “restricted securities.” A company is required to file a notice with the Commission on Form D within 15 days after the first sale of securities in the offering. Although the Securities Act provides a federal preemption from state registration and qualification under Rule 506(c), the states still have authority to require notice filings and collect state fees.” (See https://www.sec.gov/education/smallbusiness/exemptofferings/rule506c)

What are restricted securities?

According to the SEC – “Restricted securities” are previously-issued securities held by security holders that are not freely tradable. Securities Act Rule 144(a)(3) identifies what offerings produce restricted securities. After such a transaction, the security holders can only resell the securities into the market by using an effective registration statement under the Securities Act or a valid exemption from registration for the resale, such as Rule 144.

Rule 144 is a “safe harbor” under Section 4(a)(1) providing objective standards that a security holder can rely on to meet the requirements of that exemption. Rule 144 permits the resale of restricted securities if a number of conditions are met, including holding the securities for six months or one year, depending on whether the issuer has been filing reports under the Exchange Act. Rule 144 may limit the amount of securities that can be sold at one time and may restrict the manner of sale, depending on whether the security holder is an affiliate. An affiliate of a company is a person that, directly, or indirectly through one or more intermediaries controls, or is controlled by, or is under common control with, the company.

How can an investor resell non-restricted securities?

An investor that is not affiliated with the issuer and wishes to sell securities that are not restricted must either register the transaction or have an exemption for the transaction. An exemption commonly relied upon for the resale of the securities is Section 4(a)(1) of the Securities Act which is available to any person other than an issuer, underwriter or dealer. Please be aware that several exemptions, including the exemptions under Regulation D, are only available for offers and sales by an issuer of securities to initial purchasers and are not available to any affiliate of the issuer or to any person for resales of the securities.” (See https://www.sec.gov/education/smallbusiness/exemptofferings/faq?auHash=rh5WfJi9h3wRzP6X2anOmgYLdhPHNuo-3Vw0YNZyR_M#faq4)

Built in compliance options. We program a companies security token for the restricted security.

To comply with a Rule 144 safe harbor, a buy/sell lockup period is programmed into a Regulation D security token to enforce the restriction.

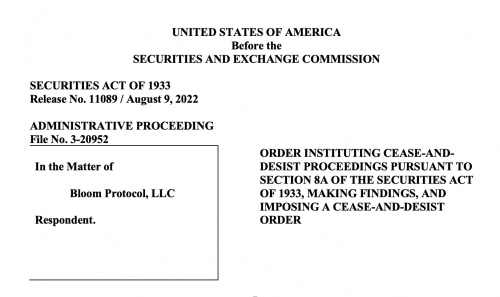

Regulation D 506(c) offerings are are subject “bad actor” disqualification provisions. It is reccomended clients hire a third-party service to execute bad actor checks. https://www.sec.gov/info/smallbus/secg/bad-actor-small-entity-compliance-guide

Note; “…an offering is disqualified from relying on Rule 506(b) and 506(c) of Regulation D if the issuer or any other person covered by Rule 506(d) has a relevant criminal conviction, regulatory or court order or other disqualifying event that occurred on or after September 23, 2013, the effective date of the rule amendments. Under Rule 506(e), for disqualifying events that occurred before September 23, 2013, issuers may still rely on Rule 506, but will have to comply with the disclosure provisions of Rule 506(e).”

…

Under the final rule, disqualifying events include:

- Certain criminal convictions

- Certain court injunctions and restraining orders

- Final orders of certain state and federal regulators

- Certain SEC disciplinary orders

- Certain SEC cease-and-desist orders

- SEC stop orders and orders suspending the Regulation A exemption

- Suspension or expulsion from membership in a self-regulatory organization (SRO), such as FINRA, or from association with an SRO member

- U.S. Postal Service false representation orders

Many disqualifying events include a look-back period (for example, a court injunction that was issued within the last five years or a regulatory order that was issued within the last ten years). The look-back period is measured from the date of the disqualifying event—in the example, the issuance of the injunction or regulatory order—and not the date of the underlying conduct that led to the disqualifying event.” (See https://www.sec.gov/info/smallbus/secg/bad-actor-small-entity-compliance-guide#part3)

Schedule an appointment to have an attorney begin the Security Token Offering process utilizing Regulation D / rule 506(c).