Blog

An STO, or Security Token Offering uses blockchains distributed encrypted ledger in the sale and transfer of a company’s stock or membership units in an LLC.

Because this token is a security under U.S. law, the rules and regulations must be followed. There could be civil or criminal liability for individuals that do not deal properly with securities. Blockchain does not provide a work-around to U.S. securities or tax laws.

There are several exemptions from Securities Act registration that make it more practical and affordable to raise funds.

In 1982, the SEC combined the exemptions for private placements and small offerings into a set of rules known as “Regulation D”. These rules give guidance on when an offering will qualify for the §4(a)(2) private placement exemption (Rule 506) and create another exemption for smaller offerings as authorized by §3(b)(1) and more recently §28 (Rule 504, amended in 2020).

With Rule 506, there is a 506(b) or 506(c) option. 506(b) will be discussed in another article.

The Rule 506(c) exemption to Securities Act Registration used to fundraise.

It is a private placement that allows an unlimited amount of funds to be raised from accredited investors. A company may advertise to everyone with 506(c), so long as equity is only sold to accredited investors.

“Rule 506(c) permits issuers to broadly solicit and generally advertise an offering, provided that:

- all purchasers in the offering are accredited investors

- the issuer takes reasonable steps to verify purchasers’ accredited investor status and

- certain other conditions in Regulation D are satisfied

Purchasers in a Rule 506(c) offering receive “restricted securities.” A company is required to file a notice with the Commission on Form D within 15 days after the first sale of securities in the offering. Although the Securities Act provides a federal preemption from state registration and qualification under Rule 506(c), the states still have authority to require notice filings and collect state fees.” (See https://www.sec.gov/education/smallbusiness/exemptofferings/rule506c)

What are restricted securities?

According to the SEC – “Restricted securities” are previously-issued securities held by security holders that are not freely tradable. Securities Act Rule 144(a)(3) identifies what offerings produce restricted securities. After such a transaction, the security holders can only resell the securities into the market by using an effective registration statement under the Securities Act or a valid exemption from registration for the resale, such as Rule 144.

Rule 144 is a “safe harbor” under Section 4(a)(1) providing objective standards that a security holder can rely on to meet the requirements of that exemption. Rule 144 permits the resale of restricted securities if a number of conditions are met, including holding the securities for six months or one year, depending on whether the issuer has been filing reports under the Exchange Act. Rule 144 may limit the amount of securities that can be sold at one time and may restrict the manner of sale, depending on whether the security holder is an affiliate. An affiliate of a company is a person that, directly, or indirectly through one or more intermediaries controls, or is controlled by, or is under common control with, the company.

How can an investor resell non-restricted securities?

An investor that is not affiliated with the issuer and wishes to sell securities that are not restricted must either register the transaction or have an exemption for the transaction. An exemption commonly relied upon for the resale of the securities is Section 4(a)(1) of the Securities Act which is available to any person other than an issuer, underwriter or dealer. Please be aware that several exemptions, including the exemptions under Regulation D, are only available for offers and sales by an issuer of securities to initial purchasers and are not available to any affiliate of the issuer or to any person for resales of the securities.” (See https://www.sec.gov/education/smallbusiness/exemptofferings/faq?auHash=rh5WfJi9h3wRzP6X2anOmgYLdhPHNuo-3Vw0YNZyR_M#faq4)

Built in compliance options. We program a companies security token for the restricted security.

To comply with a Rule 144 safe harbor, a buy/sell lockup period is programmed into a Regulation D security token to enforce the restriction.

Regulation D 506(c) offerings are are subject “bad actor” disqualification provisions. It is reccomended clients hire a third-party service to execute bad actor checks. https://www.sec.gov/info/smallbus/secg/bad-actor-small-entity-compliance-guide

Note; “…an offering is disqualified from relying on Rule 506(b) and 506(c) of Regulation D if the issuer or any other person covered by Rule 506(d) has a relevant criminal conviction, regulatory or court order or other disqualifying event that occurred on or after September 23, 2013, the effective date of the rule amendments. Under Rule 506(e), for disqualifying events that occurred before September 23, 2013, issuers may still rely on Rule 506, but will have to comply with the disclosure provisions of Rule 506(e).”

…

Under the final rule, disqualifying events include:

- Certain criminal convictions

- Certain court injunctions and restraining orders

- Final orders of certain state and federal regulators

- Certain SEC disciplinary orders

- Certain SEC cease-and-desist orders

- SEC stop orders and orders suspending the Regulation A exemption

- Suspension or expulsion from membership in a self-regulatory organization (SRO), such as FINRA, or from association with an SRO member

- U.S. Postal Service false representation orders

Many disqualifying events include a look-back period (for example, a court injunction that was issued within the last five years or a regulatory order that was issued within the last ten years). The look-back period is measured from the date of the disqualifying event—in the example, the issuance of the injunction or regulatory order—and not the date of the underlying conduct that led to the disqualifying event.” (See https://www.sec.gov/info/smallbus/secg/bad-actor-small-entity-compliance-guide#part3)

Schedule an appointment to have an attorney begin the Security Token Offering process utilizing Regulation D / rule 506(c).

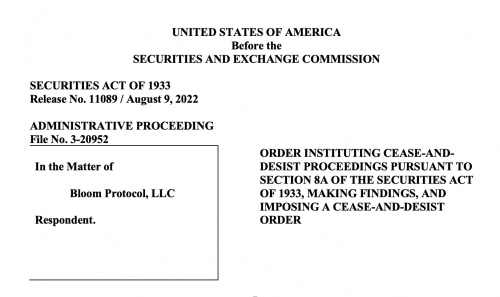

The Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) sent a cease and desist letter to Bloom Protocol, demanding it register the token as a security or face up to 31 Million in fines. Bloom quickly agreed to register and take other remedial actions.

The letters summary states;

“1. Bloom, a technology start up, was founded in August 2017 by three students and

another individual, all of whom were living in the United States. At its founding, Bloom’s

purported goal was to “revolutionize” the credit scoring industry by moving identity attestations

and credit scoring to a blockchain.

2. From November 14, 2017 to January 2, 2018, Bloom continuously offered and sold

crypto assets known as Bloom Tokens (“BLT”), which were issued on a blockchain or distributed

ledger. Bloom raised approximately $30.9 million from 7,358 worldwide investors, including U.S.

investors, through this initial coin offering (“ICO”). Bloom did not register the offering with the

Commission, nor did it qualify for an exemption to the registration requirements.

3. Based on the facts and circumstances set forth below, BLT were offered and sold as

investment contracts, and therefore securities, pursuant to SEC v. W J. Howey Co., 328 U.S. 293

(1946) and its progeny, including the cases referenced by the Commission in its Report of

Investigation Pursuant to Section 21(a) of The Securities Exchange Act of 1934: The DAO

(Exchange Act Rel. No. 81207) (July 25, 2017) (the “DAO Report”). A purchaser in the offering

of BLT would have had a reasonable expectation of obtaining a future profit based upon Bloom’s

efforts in using the proceeds from the offering to create an online identity attestation system that

would increase the token’s value on crypto asset trading platforms. Bloom violated Sections 5(a)

and 5(c) of the Securities Act by offering and selling BLT without having a registration statement

filed or in effect with the Commission or qualifying for an exemption from registration with the

Commission”

Consult an attorney that understands blockchain and securities law to help avoid issues like this.

Source : https://www.cnbc.com/2021/11/09/how-bipartisan-infrastructure-bill-will-impact-crypto-investors.html

President Biden has signed the infrastructure bill into law. CNBC’s linked article dated November 9th states the potential impact to be:

“1. Overstated 1099-Bs

One provision would require each “broker,” which will mainly be exchanges, to report their cryptocurrency gains in a type of 1099 form. “Brokers” will also have to disclose the names and addresses of their customers.

Critics worry that as written, the provision’s definition of a “broker” is too broad. Cryptocurrency advocates are concerned that the current language could potentially target those without customers who wouldn’t have access to the information needed to comply. In response to these fears, the U.S. Treasury Department said in August that it will not target non-brokers, such as miners, hardware developers and others.

However, this provision will still impact cryptocurrency investors, says Shehan Chandrasekera, certified public accountant and head of tax strategy at cryptocurrency portfolio tracker and tax calculator CoinTracker.

A “broker” or exchange must send a Form 1099-B to both the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and their customer. The customer uses information from the 1099-B to calculate their preliminary gains and losses, which is reported on their own tax return.

However, “these 1099s are going to be inaccurate for the most part, because these exchanges don’t have visibility into what you have in your self-custody wallet or what you’re doing in decentralized finance, or DeFi, applications,” Chandrasekera says. With a self-custody wallet, investors own their private keys and cryptocurrency holdings, rather than using a third party, such as an exchange. Things could get tricky if an investor has both self-custody wallets and exchange wallets.

If an investor were to send $100,000 worth of bitcoin from their self-custody wallet to their Coinbase wallet and sell the funds, Coinbase would be required to issue a 1099 saying that the investor sold $100,000. But Coinbase will not know how much the investor initially paid for the bitcoin because it didn’t happen on the exchange.

As a result, Coinbase will not know the investor’s cost basis, which may lead to an overstated 1099, Chandrasekera says.

Investors will need to sort out these inaccuracies themselves. They’re “going to get these 1099s and they’re going to panic, like, ‘Why do I have so much in gains?’” Chandrasekera says. “They will have to talk to an accountant or use a tool to reconcile it and report the right amount.”

2. Privacy and surveillance

Another provision expands a section of the U.S. tax code called 6050I to include digital assets.

Section 6050I requires that people who receive more than $10,000 in cash and equivalents file a report with the IRS. The report includes details about who paid them, including names and Social Security numbers. Any failure to report details about those sending payments is considered a felony offense.

The infrastructure bill provision would require similar from businesses and exchanges when they receive more than $10,000 in cryptocurrency.

While “it doesn’t have any direct burden on the end taxpayer,” Chandrasekera says, it will impact their privacy.

“Say you buy a Tesla with one bitcoin valued at $60,000. The car seller — the business — has to collect your personal information, like your name, address, Social Security number, etc., so they can report that to the IRS,” he says.

This surveillance rule has been called “unworkable and arguably unconstitutional” by cryptocurrency lobbyists like non-profit CoinCenter.

“Crypto people are privacy conscious. Why would they want to give all their information to these businesses? Some of these businesses may not even have a good way to protect that private information. That could lead to other second- and third-order consequences,” Chandrasekera says.

Provisions will not take effect until January 2024

The provisions will not take effect until January 2024, and in the meantime, lobbyists within the cryptocurrency industry plan to push for amendments and standalone bills to adjust the provisions.

Prior to establishing the law, the Treasury plans to take time to undergo research to understand who might be asked to comply and verify whether they’d be capable of doing so, a Treasury official previously told CNBC Make It. This process could take years.

The provisions in this bill are more to establish intent, rather than lay out specific rules.

“It’s up to the Treasury Department to decide who is subject to the provisions,” Ivory Johnson, certified financial planner, chartered financial consultant and founder of Delancey Wealth Management, says. “Similar to the ‘broker’ definition, the Treasury Department will have to provide guidance.”

Author; Chloe Diamond

(https://medium.com/sea-foam-media/tokenization-of-energy-is-the-future-7d09ded60c5b_)

While researching for this article, I couldn’t help but think about how archaic the idea of centralised energy distribution is. Large power plants providing electricity to the masses via a centralised grid seems impractical, slow, and expensive, particularly when considering the huge number of people who rely on it.

I endured many school trips to our natural gas power plants in Oxfordshire, England in which we were encouraged to start thinking about energy production and, thankfully, renewable alternatives. Despite many brainstorming sessions, I couldn’t quite comprehend the sheer scale of what I was witnessing. The plants themselves were hard to ignore in the midst of the countryside, not to mention the gargantuan amount of energy they should produce to maintain every household, which is approximately 4.648 per kWh in the UK and 10,766 kWh in the US annually.

As technology progresses, such old-fashioned approaches need to be rethought. Bringing blockchain to the energy sector has the potential to transform how people engage with these utilities by bringing control and transparency back to the end users and offering solutions for people who have been neglected by traditional systems.

Transparent Energy Costs & Crypto Payments

Until now, energy rates have been determined solely by centralised authorities, whether that’s the energy supplier or government. In California for example, the government has artificially-inflated energy rates to deter users from using particular types of energy, making it costly for those who cannot afford alternatives.

Introducing blockchain technology and cryptocurrency payments to this sector means rates can be adjusted according to supply and demand signals in the market rather than a third-party enforcer. This makes energy costs fairer and more transparent for everyone involved, and by using cryptocurrency to pay for energy the entire process will run more smoothly by eliminating slow transaction times.

Tokenizing the Energy Grid

Cryptocurrencies can also be used to tokenise the grid, facilitating a variety of energy market transactions. One example of this is Zome, which plans to reward consumers in tokens for saving energy. It will also allow building owners to generate revenue for discharging energy to the grid when demand is high.

Zome will achieve this in part through integration with IoT smart home devices and a mobile app. This will provide consumers and businesses with an effective way to track their energy usage and receive notifications when appliances are not being used optimally. Users will then be rewarded with tokens for responding accordingly.

Energy Storage as Value & Energy as a Service

As traditional energy distribution systems struggle to keep up with increasing demand, especially during peak hours, the importance of technologies like Distributed Energy Resources (DER) cannot be understated.

DERs are small-scale units of energy generation that are connected to the grid at the distribution level. They usually include (but are not limited to) rooftop solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles (EV) and EV chargers, and natural gas turbines.

The ability to store this energy is vital, not only in situations of power disruption but also as a means for people in rural areas to support their local businesses and communities. In an example from one of our partners, Energy-as-a-Service can be delivered to rural communities through portable battery packs (solar or others) to be powered up on farms for cold-chain storage and supply chain. Supply chains on the blockchain is a clear use case, but with a token solution, rural farmers can be rewarded for their participation and given greater access to these services.

Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading

Under current conditions in the sector, energy companies do not honour users for their loyalty, energy savings, or, in the case of renewables, energy generation.

Energy suppliers are able to manipulate costs however they would like due to the system and terms they’re operating under being unclear. This allows for consumers to be disadvantaged because of factors outside of their control, such as their geography, the type of fuel being generated, and the technology available in that region.

Powerledger, a Perth-based blockchain energy company, offers an alternative to this problem by allowing consumers to trade energy between themselves, providing a platform for small communities to exchange self-generated energy with ease. They have already initiated several successful trials in neighbourhoods across Western Australia, where neighbours have begun trading solar energy in a semi-regulated environment with success.

Conclusion

Although we’re just beginning to think about how blockchain could impact the energy sector, emerging initiatives already reveal how much technology could solve persistent problems within the space while improving conditions for many communities.

As increasingly more people become aware of the effect their energy consumption has on the environment, the shift towards environmentally-sound alternatives will gain more force, as well as the ability to take control over our personal energy footprint.

Managing our own domestic and corporate energy usage allows us to make informed decisions, gain transparency of the energy market, share surplus energy with our peers and liberate those who still struggle with lack of access and regular power outages. However we progress, future solutions should be adaptive and efficient, ensuring ultimate compatibility with a variety of demands and environments.

The SEC ramps up its efforts to combat digital fraud.

By Wick Sollers, Dan Sale, Christina Kung, and Kelli Gulite (https://www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/committees/criminal/practice/2019/cryptocurrency-crackdown/)

Financial services must tie these three factors together – customer experience, best practices and reliability/responsiveness – to have an effective web presence. They can’t go hard into one particular area and ignore the others. They have to understand what’s available versus their competitors, what consumers think of their sites versus competitors’ and how their sites are…

On November 2, 2018, the Enforcement Division of U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued its annual report. The report described the division’s enforcement actions and policy initiatives over the past year, highlighting the SEC’s enforcement efforts in several areas, including retail investors, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, and securities offerings. However, some of the more interesting statistics within the report outline recent efforts to combat scams in the cryptocurrency market.

According to the report, the SEC brought 20 stand-alone actions and opened dozens of investigations involving digital assets this year. This is particularly significant because the agency did not even mention cryptocurrencies in its 2016 annual report. The 2018 report also notes that the SEC has shifted resources to pursue investigations in the cryptocurrency market. Part of those resources will undoubtedly be steered toward the division’s Cyber Unit, which was formed at the end of 2017 to tackle cyber-related threats and misconduct. The Cyber Unit currently has over 225 ongoing investigations.

Most of the SEC’s efforts to combat digital fraud this year were focused on initial coin offerings (ICOs). ICOs are a recent phenomenon and can be thought of as the digital-market equivalent of an initial public offering (IPO). Instead of fundraising by selling shares, companies accept money or digital currencies such as bitcoin in exchange for “tokens” specific to the company. Tokens can take many forms but are, essentially, credits in the company.

Despite regulators’ increasing interest in the ICO market, some large corporations want to capitalize on this new technology. In 2018, Kodak launched an ICO for KODAKCoin, a currency used to buy photo rights on Kodak’s digital photography platform, KodakOne. Kodak’s stock price tripled after it announced its plans to issue an ICO. And Overstock.com raised $134 million dollars in an ICO that launched in late 2017. At the same time, other corporations are distancing themselves from the cryptocurrency market, likely due to the increased government scrutiny. For example, Google and Facebook recently banned all advertisements for ICOs from their platforms.

While corporations are uncertain about the future of digital currencies, the SEC has clearly demonstrated its intention to rein in the market for ICOs. A few weeks after the report was published, the SEC announced that professional boxer Floyd Mayweather Jr. and music producer DJ Khaled settled claims that they failed to disclose payments received for promoting investments in ICOs. In addition to investigating and prosecuting high-profile cases, the SEC has also engaged in non-conventional methods to signal that it is serious about ICO fraud. In May 2018, for example, the agency launched a mock website selling “HoweyCoins” to draw attention to the problem of ICO fraud and show how easily fraudsters can set-up a scam ICO.

The SEC has not been the only regulator to launch investigations into the digital-currency market. State attorneys general from Alabama, Colorado, Maryland, Massachusetts, Texas, Missouri, North Carolina, and New Jersey all issued cease-and-desist orders to ICOs this year. The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) also brought its first disciplinary action related to cryptocurrency in September. Additionally, the Department of Justice (DOJ) announced that it would develop a comprehensive strategy to combat cryptocurrency fraud next year.

The DOJ also scored a big win in a cryptocurrency case in 2018 in United States v. Zaslavskiy. Maksim Zaslavskiy pled guilty to ICO fraud when he initiated two ICOs that he falsely claimed were backed by investments in real estate and diamonds. While the presiding district judge said the indictment “charges a straightforward scam,” the case created monumental precedent. Before Zaslavskiy pled guilty, the court ruled that ICOs are considered securities and must comply with the registration and fraud provisions of the securities laws. As such, agencies will have the full weight of these laws to prosecute future ICO misconduct.

While it remains to be seen how receptive other courts will be to criminal cases involving cryptocurrency fraud, more investigations into the digital assets market can be expected in 2019. In fact, the Wall Street Journal recently published a comprehensive study [login required] that showed that 16 percent of the ICOs examined (513 companies) used deceptive and fraudulent tactics. Considering the rate of ICO fraud, this crackdown may only escalate the tension between crypto proponents and federal regulators.

- Blockchain (4)

- Crypto News (3)

- Finance & accounting (2)

- Regulation D (1)

- Security Token Offering (1)